PREVIOUS: JAPAN-MATSUE

LAFCADIO HEARN'S LAST YEARS

KUMAMOTO-KYOTO-TOKYO 1891 - 1904

KUMAMOTO, KYUSHU 1891-94

After the bitterly cold winter in Matsue a shivering Hearn took a teaching job at Kumamoto, "a vast, straggling, dull, unsightly

town" in Kyushu, the southern-most of the Islands of Japan. Though not "tropical" - Hearn recalls his stay in the West-Indies, Kumamoto is climatically at least bearable.

Nina Kennard describes Hearn's move to Kumamoto:

"He began to look back with regret to the days passed

in the "Fairyland" of Matsue: "You must travel out of Izumo," he told himself and find out how unutterably

different Matsue is from other places. - For instance, in this country (Kumamoto) the charming simplicity of the Izumo folk

does not exist."

All his Izumo servants had accompanied him to his new

quarters, and apparently all his wife 's family, for he mentions

the fact that he has nine lives dependent upon him :

his wife's mother, wife's father, wife's adopted mother,

wife's father's father, his servants, and a Buddhist student. Not to mention (sic!) his wife and new-born son."

From Nina Kennard,

KUMAMOTO STUDENTS 1894

Hearn found the "new reality" of Japan most startling in his students at the government college where he taught.

"The students of the Government College, or

Higher Middle School, can scarcely be called

boys ; their ages ranging from the average of

eighteen, for the lowest class, to that of twenty-

five for the highest. The best pupil can hardly hope

to reach the Imperial University before his

twenty-third year, and will require for his entrance

there into a mastery of written Chinese

as well as a good practical knowledge of

either English and German, or French.

The impression produced upon me by the

Kumamoto students was very different from

that received on my first acquaintance with

my Izumo pupils. Kyushu still remains, as of yore, the

most conservative part of Japan, and Kumamoto,

its chief city, the centre of conservative

feeling. This conservatism is, however, both

rational and practical. Kyushu remains of all districts of the

Empire the least inclined to imitation of

Western manners and customs. The ancient

samurai spirit still lives on; and that spirit exacted

severe simplicity in habits of life.

Kumamoto

is proud of all these things, and boasts of her

traditions. Indeed, she has nothing else to

boast of. A vast, straggling, dull, unsightly

town is Kumamoto : there are no quaint,

pretty streets, no great temples, no wonderful

gardens. A wilderness of flimsy

shelters erected in haste.

The Kumamoto youths, - whenever not obliged to don military uniform - still cling to a costume

somewhat resembling that of the ancient bushi. They, though born to comparative wealth, find no pleasure so keen as that of

trying how much physical hardship they can

endure.

For a long time I used to wonder But later on, at frequent intervals,

came to me suggestions of an inner life much

more attractive than this outward appearance : hints of an emotional individuality. A few I

obtained in casual conversations, but the most

remarkable in written compositions."

A lengthy description follows of his methods of teaching, of themes and questions Hearn posed to his students and their answers.

From Elizabeth Bisland, 1895

KOBE and KYOTO 1894-96

After Kumamoto Hearn took another teaching job at Kobe, a military garrison town and naval harbor neither pretty nor quaint. He lived with his wife and child in a pretty enough house high above Suma Beach, immortalized by the Genji and the Heike Monogatari. Nevertheless he hated Kobe, and all his black visions resurfaced.

.

THE TIME OF THE CHOLERA 1894

"Cholera had come with the victorious Japanese army from

China, and had carried off, during the hot season, about

thirty thousand people.

Sometimes the smoke and the odor

come wind-blown into my garden down from the

hills behind the town.

From the upper balcony of my house, the whole

length of a Japanese street, with its rows of little

shops, is visible down to the bay. Out of various

houses in that street I have seen cholera-patients

conveyed to the hospital - the last one (only this

morning) my neighbor across the way. He was removed by force, in spite

of the tears and cries of his family. The sanitary

law forbids the treatment of cholera in private

houses; yet people try to hide their sick. My neighbor's wife followed the litter,

crying, until the police obliged her to return to

her desolate little shop.

The children sport as usual. They chase one

another with screams and laughter; they dance in

chorus; they catch dragon-flies and tie them to long

strings; they sing burdens of the war, about cutting

off Chinese heads.

A pipe-stem seller used to make his round with

two large boxes suspended from a bamboo pole balanced

upon his shoulder: one box containing stems

of various diameters, lengths, and colors, together

with tools for fitting them into metal pipes; and

the other box containing a baby — his own baby.

The other day I discovered that he

had abandoned his bamboo pole and the suspended

boxes. He was coming up the street with a

little hand-cart just big enough to hold his wares and

his baby, evidently built for that purpose with

two compartments. The

child seemed well and happy. Among its toys I noticed a

tablet-shaped object. It was fastened upright to a

high box in the cart facing the infant's bed.

There was no mistaking the tablet

was a Shinshu ihai, a memorial tablet bearing a woman's kaimyo, or

posthumous name.

With the help of our maid the pipe-stem seller told us his story:

Two months after the birth of their little boy, his

wife had died. In the last hour she had

asked him: "From the time I die till three full years be

past I pray you to leave the child always united

with the Shadow of me: never let him be separated

from my ihai, so that I may continue to care for him

and to nurse him."

The pipe-stem seller could not afford to buy milk; but he had

fed the boy for more than a year with rice gruel and

ame syrup.

I said that the child looked very strong, and none

the worse for lack of milk. "That," he declared in a tone of conviction bordering on reproof, "is because his dead

mother nurses him. How should he want for milk?"

And the boy laughed softly, as if conscious of a

ghostly caress".

From Elizabeth Bisland. 1922

KOBE 1893 - 1896

Hearn, Setzu, and Kazuo in Kobe, 1893

Photo from trussel.com

Hearn was now married. He was gaining weight. His wife took happily credit for it. Little Katsuo was growing fast. Lafcadio was teaching English literature in another middle school.

THE ETERNAL FEMININE 1896

"Teacher, please tell us why there is so

much about love and marrying in English

novels ; - it seems to us very, very strange."

This question was put to me while I was trying

to explain to my literature class - young

men from nineteen to twenty-three years of

age - why they had failed to understand certain

chapters of a standard novel, though they were quite

able to understand the logic of Jevons

and the psychology of James.

Under the circumstances,

it was not an easy question to

answer. As it was, though

I endeavored to be concise as well as lucid,

my explanation occupied something more than

two hours.

Any social system of which filial piety is not

the moral cement ; any social system in which

children leave their parents in order to establish

families of their own ; in which it is considered not only natural but

right to love wife and child more than the

authors of one's being; any social system in

which marriage can be decided independently

of the will of the parents, by the mutual inclination

of the young people themselves ; in which the mother-in-law is not

entitled to the obedient service of the daughter-

in-law, appeared to them of necessity a state

of life scarcely better than that of birds and the beasts of the field, at best a sort of moral chaos.

To the young Japanese,

marriage appears a simple, natural duty,

for the due performance of which his parents

will make all necessary arrangements at the

proper time. That foreigners should have so

much trouble about getting married is puzzling

enough to them ; but that distinguished authors should write novels and poems about

such matters, and that those novels and poems

should be vastly admired, puzzles them infinitely

more, - it seems to them put politely " very, very

strange." His real thought would have

been more accurately rendered by the word "indecent."

Now, where passionate love is the theme in

Japanese literature, it is not the

love which leads to the establishment

of family relations. It is quite another

kind of love - about which the

Oriental is not prudish at all, - the mayoi,

or infatuation of passion, inspired by

physical attraction. Its heroines are not

the daughters of refined families, but

hetaerae, or professional dancing-girls....

Let the reader

reflect for a moment how large a place the

subject of kisses and caresses and embraces

occupies in our poetry and prose

fiction ; and then let him consider the fact that

in Japanese literature these have no existence

whatever. For kisses and embraces are simply

unknown in Japan as tokens of affection."

Hearn, the shy Irish-Greek man sums up his 40-pages-long eloquent plaidoyer for Japanese virtues with the sentence:

"Western worship of Woman as the Unattainable,

the Incomprehensible, the Divine, the

ideal of " la femme que tu ne connaitras

pas," — the ideal of the Eternal Feminine

does not exist at all in the Orient."

He then considers the far reaching consequences of this principle not only for literature but for all Art, Western compared to Eastern.

In her introduction to Hearn's letters Elizabeth Bisland, his most intimate, shunned friend of his years in New Orleans, described his view of women:

"Hearn's attitude towards women, so misinterpreted by

vulgar minds, had its origin in this mystic sense of

her being the channel of heredity. In a sense of the

tenderness of eternal motherhood in her smile, of

the transmission of a million caresses in her fairness -

a fairness which had blossomed through the nurturing

warmth of endless aspiration toward beauty

and love."

Elizabeth Bisland, 1910

The quotation from the Eternal Feminine is found in Lafcadio Hearn, "Out of the East, Reveries and Studies in New Japan," 1895

KYOTO, HEARN' S ROMANTIC DREAMS OF JAPAN. 1895-96

To Hearn the consolation during his teaching at Kobe seems to have been the closeness of Kyoto. Whenever time permitted he took refuge at a charming, old-fashioned hotel there where he spent long weeks of dreaming of the Old Japan:

FROM A TRAVELING DIARY

Kyoto, April 16, 1895

"The wooden shutters before my little room

in the hotel are pushed away ; and the morning

sun immediately paints upon my shoji, across squares of gold light, the perfect sharp

shadow of a little peach-tree. No mortal

artist - not even a Japanese - could surpass

that silhouette! Limned in dark blue

against the yellow glow, the marvelous image

even shows stronger or fainter tones according

to the varying distance of the unseen branches

outside. It sets me thinking about the possible

influence on Japanese art of the use of

paper for house-lighting purposes.

By night a Japanese house with only its

shoji closed looks like a great paper-sided lantern, -

a magic-lantern making moving shadows

within, instead of without itself. By day

the shadows on the shoji are from outside

only; but they may be very wonderful at the

first rising of the sun, if his beams are leveled,

as in this instance, across a space of quaint

garden."

From Lafcadio Hearn, "Kokoro, Hints and Echos of Japanese Inner Life", 1896

His best Japanese essays in the collection "Kokoro" (The Heart) were written in Kyoto : "Notes from a Travelling

Diary," "Pre-Existence, " and the charming sketch "Kimiko," all originated in Kyoto.

Nina Kennard, 1920

Photo RWFG

KOKORO 1896

is a collection of stories and reveries on Japan's past which Hearn wrote during the years he taught in Kobe. His infatuation with Japan's culture, his preoccupation with the supernatural, moved beyond tears by its beauty he puts into words the unreal reflections of his romantic view - as do the photos I addedd - all taken during the one day I ever spent in Japan, at Narita Shan on a lay-over on a flight from Beijing to Los Angeles....

Lafcadio Hearn, "Kokoro" edited by Elizabeth Bisland, 1896

Photo RWFG

KIMIKO 1896

The story of a geisha who loses her love. One of the most romantic, heart-rending of Hearn's stories. :

See

"Kimiko", edited by Elizabeth Bisland, 1986

Photo RWFG

THE IDEA OF PREEXISTENCE

Hearn's musings on the most fundamental philosophical theme of the Buddhist Far East.

"Were I to ask any reflecting Occidental, who had

passed some years in the real living atmosphere of

Buddhism, what fundamental idea especially differentiates

Oriental modes of thinking from our own, I

am sure he would answer: "The Idea of Preexistence."

It is this idea, more than any other, which

permeates the whole mental being of the Far East.

It is universal as the wash of air: it colors every emotion;

it influences, directly or indirectly, almost

every act. Its symbols are perpetually visible, even

in details of artistic decoration; and hourly, by day

or night, some echoes of its language float uninvited

to the ear. The utterances of the people - their

household sayings, their proverbs, their pious or profane

exclamations, their confessions of sorrow, hope,

joy, or despair - are all imbued with it."

Quoted from "The Idea of Pre-Existence" edited by Elizabeth Bisland, 1922

Photo RWFG

TOKYO 1896-1904

Lefcadio Hearn's Last Years.

Tokyo Imperial University 1896-1903

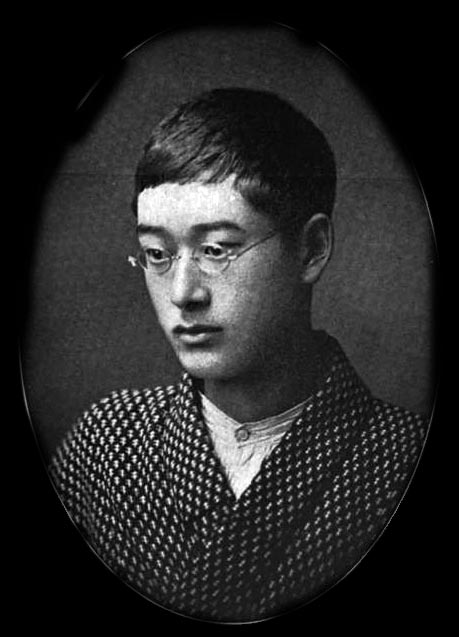

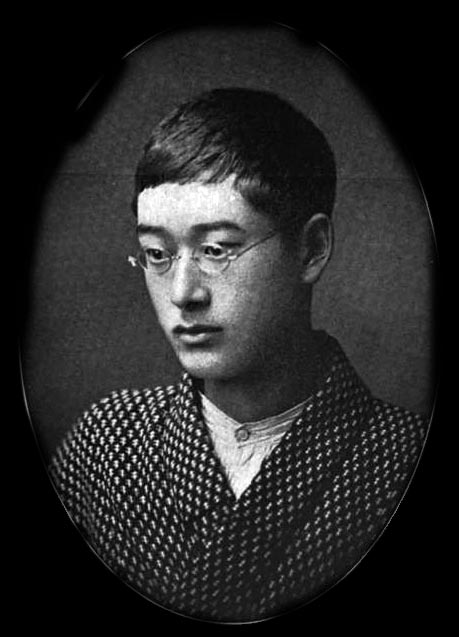

Lafcadio Hearn at Tokyo University 1896-1903

Photo trussel.com

Lafcadio Hearn taught English literature at Tokyo University from 1896 to 1903.

Many literati were among his students: like Ueda Bin, Osanai Kaoru, Doi Bansui.

In 1896 he moved his family from Kobe to Tokyo where

he bought a simple house without garden at 21, Tomihasa-chio, Ichigaya, situated in Ushigome, a suburb of Tokyo until 1902 and taught at the Imperial University of Tokyo. The house no longer exists and only a memorial marker remains.

Waseda University

In 1903 Hearn was appointed to teach English literature at Waseda University.

Though he taught here only half a year, he influenced students like Ogawa Mimei, and made a good friend of Japanese writer Tsubouchi Shôyô, a professorial colleague .

In 1902 Hearn left his house at Ichigaya-Tomihisa-chô and moved to 266, Nishi Okubo close to Waseda.

In 1903 he quit the Imperial University job and taught only at Waseda University

The house no longer exists and only a momorial marker remains. The notation "Here lived Lafcadio Hearn" was written by Edmund Blunden.

Today the monument is located inside the fence of Seijo-Gakuen Women's High School.

Hearn's garden in Tokyo

The writing room he added to the house . His children playing on the verandah.

Kazuo and Kiyoshi in Tokyo, 1901

Photos from Elizabeth Bisland, 1906

YAIZU SUMMER 1904

Hearn spent the summer of 1904, his last before he died of a heart attack, at Otokishis's in Yaizu on the coast teaching his two sons swimming. His wife and their little daughter remained in Tokyo.

After obtaining Japanese citizenship, Hearn used his Japanese name Kazuo Koizumi. (His oldest son is also named Kazuo or Kadzuo in Hearn's letters).

Elizabeth Bisland, op.cit., has collected the letters to his wife from this summer.

I copy a few, They are mere notes, but afford a rare glimps into his private, intimate relationship with his wife and family.

LETTERS TO MRS. HEARN

Yaizu, July 12, 1904.

LITTLE MAMMA, — To-day we have not much sunlight,

but I and Kuzuo swam as usual. Kazuo

played a torpedo in the water. He is growing clever in

swimming, to my delight. We had a long walk

yesterday. We bought a little ball and bell for the

cat whose life I had saved and brought home.

The

stone-cutter is showing me his design of the Jizo's

face. Shall I let him carve the name of Kazuo

Koizumi somewhere on the idol? I can see how glad

the Yaidzu people would be to see the new idol.

We have too many fleas here. Please, bring some

flea-powder when you come. But this little delightful

cat makes us forget the fleas. She is really funny.

We call her Hinoko.

Plenty of kisses to Suzuko and Kiyoshi from

Papa.

August 1. 1904.

Little Mama, - Yesterday we had a real big

wave, at the height of the summer season. Otokichi

swam with Kazuo, as he was afraid for Kazuo to go

alone. The sea began to groan terribly since noon;

and at evening the billows grew bigger, and almost

reached the stone wall. It is difficult to swim

this morning also, but I expect that the sea will be

calmer in the afternoon.

The little baby sparrow which I already wrote

you about had been pretty strong for the last three

days; but under the sudden change of weather it was

taken ill.

Last evening Otokichi bought two sharks. Kazuo

studied their shapes carefully; and it was the first

experience for him. Otokichi cooked nicely for our

supper shark's meat, which was white and excellent.

I take some milk in the morning.

August 10. 1904.

Little Mama San, - This morning we had a

pleasant swimming, the sea being warm. Kadzuo

did not swim so well as before, but I think he will

improve in a few days. I noticed his wearing a tiny charm, and asked him what it meant. He answered

that mother, from her anxiety for him, had told him

to wear it whenever he go a-swimming. Iwao swam

a little. He will become a good swimmer.

Ume [Otokichi's son] is now a grown man and

even married. His wife is kind and lovely. This

year Otokichi looks a little older than before. As

to the rampart here, it was the old one that had

got some damage; the new one is very strong. It

is a pity that those ducks and doves are seen no

more.

Loving words from Papa to dear Mamma and

Grandmother.

August 24, 1904.

Little Mama, - Yesterday it was so hot; the

thermometer rose to ninety-one degrees. However,

the winds blew from the sea at night. And this

morning the waves are so high, I only take a walk.

Otoyo gave the boys plenty of pears. Last evening,

Kazuo and Iwao went to a shooting gallery for fun.

We drank soda and ginger ale, and also ate ice.

Iwao has finished his first reader; it seems that

learning is not hard for his little head at all. He

studied a great deal here. And he is learning from

Mr. Niimi how to write Japanese characters.

Just this moment I received your big letter. I

am very glad to hear how you treated the snake you

mentioned. You were right not allowing the girls

to kill it. They only fear, as they don't understand

that it never does any harm. I believe it must be

a friend of Kami-sama in our bamboo bush.

Mr. Papa and others wish to see Mamma's sweet

face. Good words to everybody at home.

Yakumo.

From Elizabeth Bisland, 1910

On September 26, 1904 Hearn died of a heart attack

In a letter written to Mrs. Atkinson - Lafcadio's half-sister by his father's second marriage - some months after

Lafcadio's death, Mrs. Koizumi, his wife, describes his last

hours : "On the evening of September 26th, 1904, after supper,

he conversed with us pleasantly, and as he was about going

to his room, a sudden aching attacked his heart. The pain

lasted only some twenty minutes. After walking to and

fro, he wanted to lie down; with his hands on his breast

he lay very calm in bed, but in a few minutes after, as if

feeling no pain at all, with a little smile about his mouth,

he ceased to be a man of this side of the world. I could

not believe that he would die so sudden. It was his fate."

From Nina Kennard, 1912

LEFCADIO HEARN'S BUDDHIST FUNERAL

A detailed account was given of the funeral by an

American lady, a Miss Margaret Emerson. The funeral procession started from

his residence, 266, Nishi Okubo, at half-past one on September

29th, 1904 and would proceed the 1000 meters to the Jitom Kobduera

Temple in Ichigaya, where the Buddhist service was to be

held. It was one of those luminous Japanese days that had

so often inspired him. Not a cloud veiled the pale azure of the sky. Only the solitary cone of Fuji-yama stood out, a "ghostly apparition"

between land and sea.

He was carried to his last resting-

place preceded by a priest ringing a bell, men carrying

poles, from which hung streamers of paper gohei; others

bearing lanterns and others again wreaths, and huge

bouquets of asters and chrysanthemums, while two boys

in rickshas carried little cages containing birds that were

to be released on the grave, symbols of the soul released

from its earthly prison. Borne, palanquin-wise, upon the

shoulders of six men, of the caste whose office it is to dig

graves and assist at funerals, was the coffin, containing

what had been the earthly envelope of that marvellous combination of good and evil tendencies, the soul of Lafcadio

Hearn.

While the temple bell tolled with muffled beat, the procession

filed into the old Temple of Jitom Kobduera. The

mourners divided into two groups, Hearn's wife, who,

robed in white, had followed with her little daughter in

a ricksha, entering by the left wing of the temple, while

the male chief mourners, consisting of Kazuo, Lafcadio's

eldest son, Tanabe (one of his former students at Matsue),

and several university professors, went to the right.

Kazuo, Lafcadio's oldest son at 17.

Then followed all the elaborate ceremonial of the

Buddhist burial service. The eight Buddhist priests

dressed in magnificent vestments chanted the chant of the

Chapter of Kwannon in the Hokkekyo.

After the addresses to the soul of the dead, the chief

mourners rose and led forward Hearn 's eldest son; together

they knelt before the hearse, touching their foreheads

to the ground, and placed some grains of incense

upon the little brazier burning between the candles.

The

wife, when they had retired, stepped forward, leading a

little boy of seven, in a sailor suit with brass buttons and

white braid. She also unwrapped some grains of incense

from some tissue paper, and placed them upon the brazier.

Then, after a considerable amount of bowing and chanting,

the ceremony ended and the congregation left the

temple.

Text and photo from Nina Kennard, 1912

THE END

RETURN TO THE INTRODUCTION